Rebecca Ackroyd’s work revolves around the interplay of conscious and subconscious, past and present, personal and collective experience. Now, the first monograph about the artist is published by Distanz Verlag – with essays by Attilia Fattori Franchini, Alexander Wilmschen, and an interview with the artist. Speaking of interview – Fräulein talked to Rebecca Ackroyd for issue #37 – NEW WOKE. Read about her vision here.

Rebecca Ackroyd: “When you change, your memory changes”

“Memory can only be a fragment as we cannot see our lives as a whole and, also, our memory transforms with time as our perception of an event transforms. When you change, your memory changes.”

Dozens of giant eyes from canvases gaze upon those standing in the center of Rebecca Ackroyd’s studio in Berlin, seeming to dissect every aspect of being. A feeling of unease is in the air, characteristic of the British artist’s work, although her pieces simultaneously captivate with colorful beauty. It is the interplay of the sexual and the ethereal, the seductive and the repulsive, the airy-light and the abyssal dark, that casts a spell over viewers and afterwards reverberates like an echo.

Spiritual wisdom weaves through the paintings and sculptures as seamlessly as theories of psychoanalysis, revealing the sheer complexity of human experience. Prior to the showcasing of Rebecca Ackroyd’s work in the supporting program of the 2024 Biennale, Fräulein sat down with the artist for a conversation – exploring the interplay of conscious and subconscious, past and present, and the question of whether there is such a thing as absolute truth in human existence.

Period Drama. Kestner Gesellschaft. Install View, 2023.

Period Drama. Kestner Gesellschaft. Install View, 2023.

Fräulein: How would you describe the main themes of your work?

Rebecca Ackroyd: My work is very layered. I extract ideas from everything. From personal experience, for sure, as I like things to feel very intimate. Often, I’m delving into my maternal history. I’ve used my mum’s maiden name in works to reflect the erasure of a name through marriage. I wanted to bring her name back as an object, so that it would become a sculptural totem.

But I also use general experiences for my work. So, when I show casts of my legs next to casts of my mum’s legs, they are always cut off, so that they don’t have an identity. They become representatives for women in general and, ultimately, people in general.

Your parents were both doctors, so you didn’t grow up in an artistic household. Nevertheless, at least your mother seems to be an important source of inspiration for you.

I’m really interested in storytelling and building a sense of self through understanding the past and connecting it with the present. In some ways, I’m analyzing my own history, but it’s not necessarily always that personal. A conversation with my mum made me think of the many fragments of one person’s life.

When I subsequently read The Years by Annie Ernaux, it made me think about the accumulation of time (1941-2006) through diary entries. Through her journaling, the day-to-day life of an ordinary woman in France becomes a historical document. What it also shows: The ordinariness of life can be extraordinary in itself. What may seem like a boring story of just one person at first is actually so fascinating to listen to because everyone’s experience is so different.

From single fate to big picture: By telling the story of an individual, one simultaneously reveals a lot about the circumstances and mechanisms in which they had to act, and from this, we can all draw insights for ourselves.

I’m interested in the intimacy of individual experience and how that relates to a more collective experience, especially in relation to a particular moment in culture. Considering the reliability of memory and how a personal account becomes imbued with emotion and how that distorts the reality of an event or experience. Memory can only be a fragment as we cannot see our lives as a whole and, also, our memory transforms with time as our perception of an event transforms. When you change, your memory changes.

Sometimes, I deal with these concepts in a very explicit way; sometimes, I like it to be more enigmatic. I’m present in and distant from what I’m doing at the same time. I never wanted to become autobiographical because I never wanted my work to become too literal.

“It’s fascinating how these stories that we tell ourselves shape the way we think about who we are.”

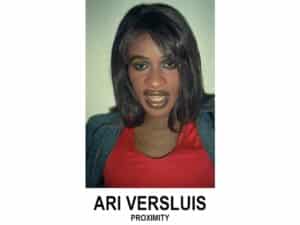

Sinead; Singer, Activist, 2024

Do you think there even is such a thing as truth?

Each of us has always had our own truth. But especially nowadays, I hear this phrase more and more often: “my truth.” It’s as if people treat their version of what is happening as if it were fact. There’s a conflation of fact and opinion, but then the idea of ‘a fact’ is malleable in itself, which I find interesting in relation to memory; it’s fascinating how these stories that we tell ourselves shape the way we think about who we are.

You’re also strongly influenced by the insights and theories of psychoanalysis. Where in your work does that become apparent?

I don’t want to get locked down in theory too much in my work. Instead, it’s about mining ideas or mining memories in order to make sense of the present. But the work I exhibit in Venice, for example, is titled “Mirror Stage,” which refers to Lacanian ideas about recognizing oneself in the mirror. This is such a fundamental development step in every child’s distinction between the self and others. But what also plays a role is the idea of fragmentation of an image or a body.

After all, in a mirror, you can never see yourself fully.

If we’re already talking about mirrors: Eyes are the mirror to the soul. And they play an important role in your works.

True, the eyes are an ongoing series within my body of work. The eye is how we perceive visually what is around us. But what is behind the eye? It’s like the gateway from the conscious to the unconscious. I see the series like these windows into the mind of a particular person who might influence or inform the cultural landscape, or who has been significant in “making,” somehow. Sometimes, I draw inspiration from my personal life, and at other times, I’m just inspired by the people shaping our cultural scene. I painted my mum’s eye, but I also painted the eyes of Pamela Anderson and Louise Bourgeois.

“A word becomes meaningless to the point of being just a sound the more times you repeat it.”

Period Drama. Kestner Gesellschaft. Install View, 2023.

Period Drama. Kestner Gesellschaft. Install View, 2023.

How do you view the interaction between consciousness and unconsciousness?

That relates a lot to the concepts of abstraction and figuration in my work. There’s a blurring of what comes from a conscious thought and what comes from a subconscious thought. I’m interested in the space of not knowing where an idea or image has come from. There’s a directness in the act of drawing that transfers from the mind to the page – it’s a sense of losing control. It’s irrational. Then there are moments where I like to be very literal or direct in the content I use. From an artistic standpoint, it’s interesting where the two sides meet and fight. Who’s got control of what is happening?

The duality between conscious and subconscious is different for the individual than for society as a whole. As an individual, it makes sense to listen to your feelings. But as a society, it would be better to be more rational.

Because the way I work is a lot about living in the space of not knowing, there’s an idea of remaining in the present that is very important to the process. I think, in a wider sense, this can also be helpful in relation to the world in general and the sense of precariousness.

With my recent show, Period Drama, at Kestner Gesellschaft, I wanted the installation of the show to reflect this idea of not knowing, so all the sculptures in the exhibition were constructed in the space with no prior planning. I wanted the works to retain a sense of energy that is sometimes lost between the studio and the exhibition space. It was a way to relinquish some of the control over the work and the exhibition in general and create works that I felt had a closer relationship to the freedom of drawing. It had a special energy that I think it wouldn’t have had if I had controlled it too much.

Although it’s not explicitly shown, one still gets the feeling that there’s a subtle sexuality present in your work. Would you agree with that?

It’s something that is certainly present, but it isn’t forced. There’s a conversation between hardness and softness that I’m interested in – between a body and a machine. Enlarged fishnet tights become like fences blurring body and boundary; I want the works to exist between attraction and abjection, the familiar and the abstract. I think about the mechanization of the body and the idea of abstraction through repetition, and losing the sense of meaning.

A word becomes meaningless to the point of being just a sound the more times you repeat it. I’ve related that in the past to learning a new language. In the beginning, you’re just saying sounds until they start to mean something, to take on familiarity and feeling. Similar to what I want to achieve with my shows: They have to make you feel something.

Interview by ANN-KATHRIN RIEDL