Since she arrived on the art scene in the 1960s, British artist Anne Bean has been a pioneer in the realms of performance art and more. Her different means for expressing her work range from political to feminist issues. Can art, Bean asks herself, prevail to challenge the male mindset that has dominated our culture for centuries?

Having moved from Livingstone, Zambia to then studying in Cape Town, South Africa and finally relocating and finishing your studies in Reading, England, how did your moves affect your early work and inspiration? How did you visualize your art back then as a female artist and what were your themes?

I painted a lot as a young artist at high school, influenced by movements like Fauvism, The Blue Rider and Expressionism, as well by the colors and vibrancy of the local African dress materials, bead work and decorative wall painting. I was always frustrated that the outcomes of my work didn’t seem to fulfill the imaginative leaps taken during the painting process. Arriving in England in late 1960’s was thrilling for me as I became aware of the heady mix of art possibilities rapidly unfolding in the zeitgeist. Boundaries were transgressed between visuals, sound, writing, consciousness-raising, activism and alternative life-styles.

Having arrived from the toxicity of apartheid South Africa, I was wary of how labelling, definition and difference impacted a country and I wanted to be more present to my own being as an artist within an art community rather than defining myself as a female artist. In a way, in England, I felt like an explorer in a not-strange land. My interior landscape and the outside world seemed, at that point, to have a familiarity with one another. I wanted to be fully present to these possibilities and to dive into the edges of both the inner and outer pulses.

You are one of the pioneers in performance art, how important is performance art as a woman? Especially touching upon feminist ideas and issues in your work.

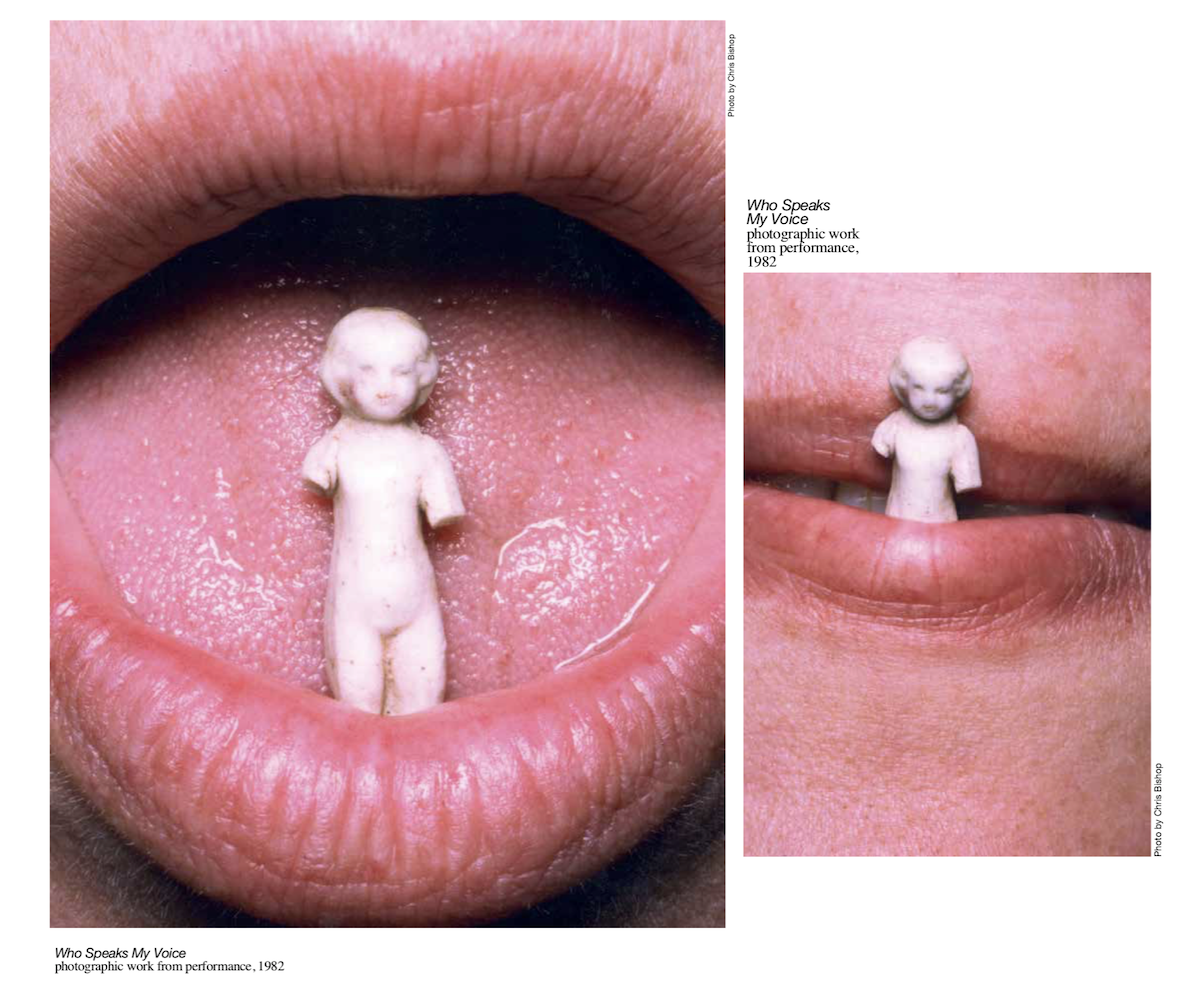

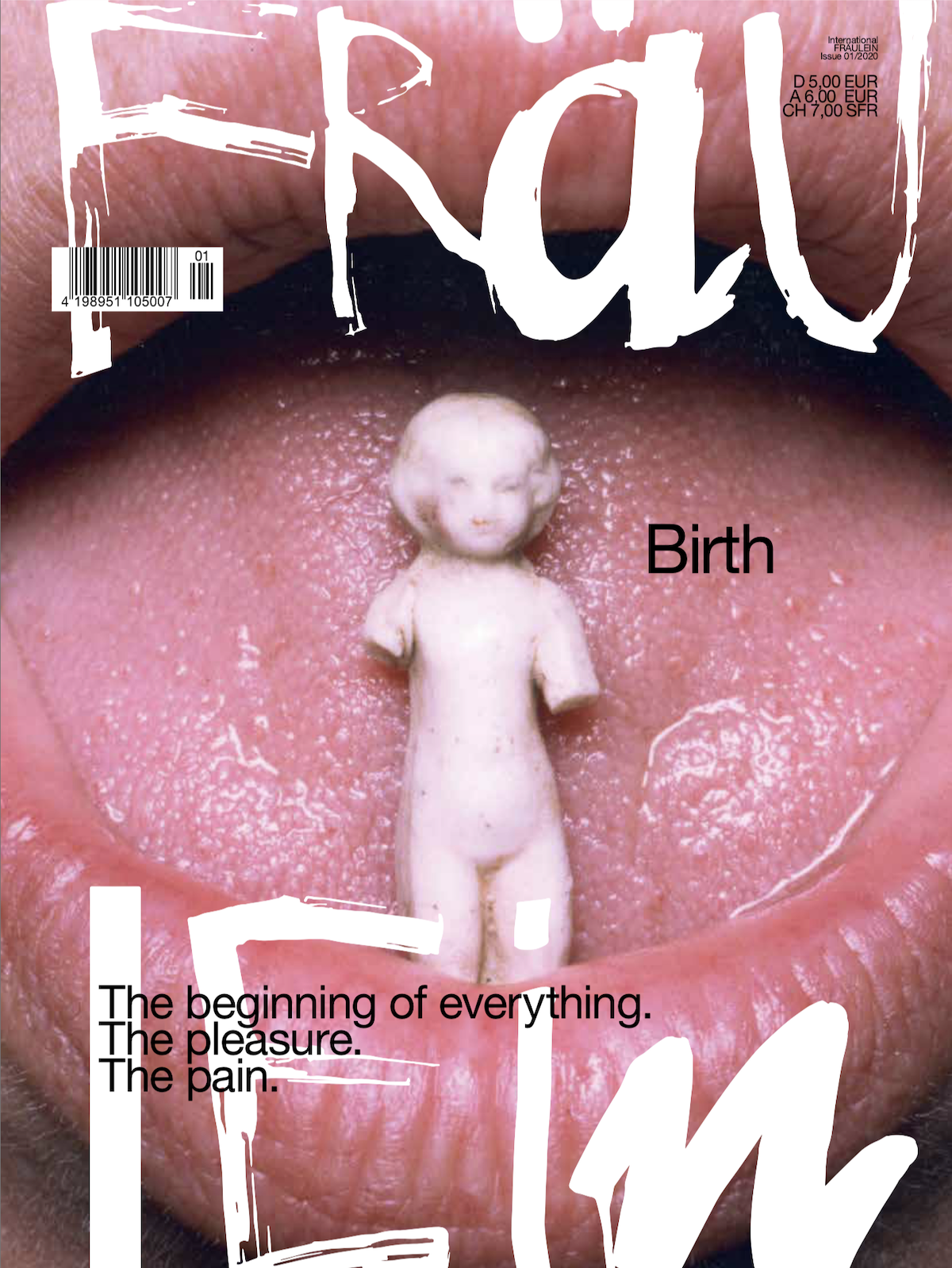

At Reading University Fine Art department, as part of what had normally been a traditional life-drawing class, in 1970, the artist and tutor Rita Donagh initiated a space for us, her students, to reflect on and question our relationship to the model and, by extension, to art history and all the inherent implications. She stimulated the awareness of the model as a human being in the space, a living being with a particular story and not just a fleshy form. We had a large studio and the model was assigned to us for three weeks. We were excited by the potential and openness of the situation. Initially, I was aware of our eyes, our pencils, connecting to the model’s body and thereby each other, as we contemplated her in this freed-up, lateral-thinking space. She told us she was a mother. She had given birth. Her breasts, her belly, her genitalia held narratives which emphasized the fact that we were drawing life, as opposed to life drawing.