Ethereal is the first word that comes to mind when meeting Agnes Questionmark. Delicate features, a soft voice and gentle demeanor make her seem like she’s from another world – even beyond her art performances, installations and sculptures. With these, Agnes Questionmark not only challenges our preconceived notions of gender and identity, but also transforms our conception of a human being into a hybrid, undefinable creature with fluid possibilities. Her art transcends boundaries, questioning the blurred lines between human, creature and machine.

Agnes Questionmark: When the patient becomes the doctor

In various ways, the artist from Rome, Italy, investigates the possibility of transcending the limitations of our given physiognomy. Whether it’s bringing to life Agnes Questionmark, a genderless half-human half-cephalopod creature, during 184 hours of performance over the course of 23 consecutive days, being destroyed in the process of birthing little hybrid beings in the operating theater, or ending up in a cadaver bag as a failed scientific experiment. Through this visceral work, the artist invites viewers into a realm of boundless imagination and existential inquiry.

No wonder that Agnes Questionmark has been acclaimed as one of the most celebrated art stars of the moment. Fräulein spoke with her ahead of the 60th Venice Biennale, that marked a significant milestone in her career.

“Science and politics want to control the human body. Instead, nature is always about versatility, adaptability and transformation.”

Photography RONALD DICK Eyewear KUBORAUM Bracelet OBJECTS INNERRAUM

Fräulein: So many heated debates are taking place in our world right now. While some of them lead to progress, fronts have become hardened. Now, the question is: What comes next? How can we bring people back to the table?

Agnes Questionmark: Traveling so much, I realized that we as humans are so different – different aims, different experiences, different urges. We need to respect each other, although we can’t expect to understand every opinion. What I feel right now is a common desire to create something new. The system has failed. And, therefore, we have to create a new one. But what should the new system look like? We don’t know yet.

It’s like we see that something new is beginning, but we are still having a lot of fights about which direction to move in. Are steps backward always a part of greater progress?

I’m even more interested in the concept of failing because it’s so important how you deal with it. I have done a series of performances called “Attempts.” They’re scientific attempts to create a new species, an alien hybrid species. But, in my experience, they always go wrong as the creatures die. No oxygen? Not enough pressure? There just aren’t the right conditions for them to live.

My attempts show the failure of science in representing a humanity that cannot be represented.

They are a critique on normative society that doesn’t allow Queer people to live their queerness fully. For example, there are so many laws and rules that stop queer reproduction. But if we don’t allow queer reproduction, we will continue to be very normative.

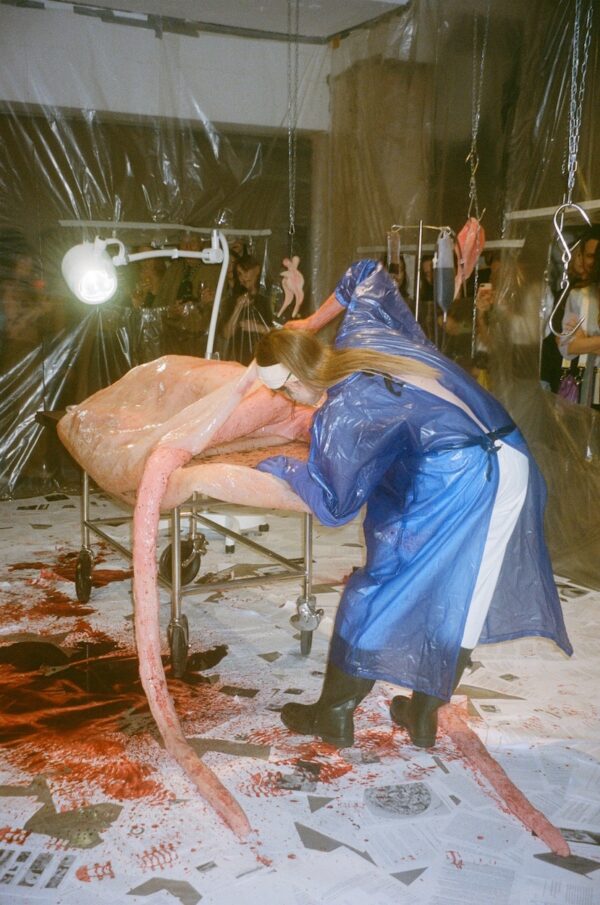

Transgenesis, curated by The Prange Garden, 2021, by Henri Kisielewski

S.A.M (SLAUGHTERING ARCHIVAL MACHINE), 6 channel video installation and silicone sculptures, Malta Biennale, by Julian Vassal

Why does queer reproduction hold this symbolic value for you?

Queer reproduction challenges society. After all, queerness is a discourse that is always embedded in technology, artificiality and theatricality. This is scary for normativity that tells people: You are born with a certain body and therefore you need to follow a sort of natural order. Even though this natural order, this purity, never even existed.

We can’t categorize human existence. We need new terminologies and a new understanding of it in all its nuances and opacity. But science and politics want to control the human body. It starts with the womb of women, but we also see it in queer reproduction, artificial insemination and artificial reproduction.

Nature, instead, is always about versatility, adaptability and transformation.

The pressure to assimilate to our binary society stands in the way of this, doesn’t it?

Yes, totally. But, to me, it’s hypocritical of normative society to defend an idea of nature that is destroyed by this very society. Let’s talk about animal reproduction, meat production and food production in general – all of nature’s purity ceases to exist there. Humans do wild things. They are ruthless. The idea of the slaughterhouse itself is ruthless. And if you apply those mechanisms to human reproduction, it really gets scary.

“We all believe in mystery, to some extent. And that is what art is for – to bring this uncanniness forward, provoke and challenge your preconceived structures.”

CHM13hTERT, performance and installation, @Spazio Serra curated by The Orange Garden and Spazio Serra, supported by Kuboraum, 2023

Do you think it’s inherent in humans that we always seek simplification and deny the complexity of things? Is this an urge we always have to fight?

You know what gives me hope in humanity? Even though people love simplicity and long for boxes to put things in, they are excited when they see my work. My work knows no class, no race, no gender. Yet everyone gets it, somehow.

It seems there is an emotional layer in your work that speaks to people.

We all believe in mystery, to some extent. And that is what art is for – to bring this uncanniness forward, provoke and challenge your preconceived structures. I’m here to shake it. Yeah, like an earthquake.

Is this also the reason why you decided to share your personal story of transitioning and de-transitioning in the most open way possible?

I’m like an open door anyways. Maybe because I grew up in a house without doors. In my family’s home, there was only one door for the bathroom and it was broken. So there was no privacy. Only when I moved out, I understood that we all need our personal space and a door to lock up behind us. I had to learn to separate my personal life from my public life and from my art.

“When you see fish or another sea creature, you don’t ask yourself if that’s a male or a female. The underwater world is such a fluid place.”

Photography RONALD DICK Eyewear KUBORAUM Bracelet OBJECTS INNERRAUM

Why was it important for you to learn that?

Because I had to be just by myself to come to the conclusion that I have to remove my breast implants. In the way I transitioned, I was chasing an ideal. I wanted to be this desirable creature. But it was more for other people to consume than something I really felt inside. This was not my mistake. The problem was: I saw myself not with my own eyes, but with the eyes of society.

So, you thought if your body is desirable, you’ve achieved your goal? As if your body only exists for the gaze of others?

This is an extremely delicate and important conversation within the transgender community. Because of the binarism of society, of body representation and of body politics, trans people get trapped in this system and they start to see their body with the eyes of others. With the gaze of a normative society. With the male gaze. I’m so fluid in my work, but even I got trapped in that. I never imagined this would happen.

I had to recognize I was making a mistake and I was failing. I opened up about it and all my friends freaked out. They were like: Are you really sure you want to switch from one to the other within two weeks?

Was there one specific moment when you realized that your transition had gone too quickly and in a direction that didn’t feel true to yourself?

It was during a performance in Milan. So many people stared at me while I was suspended for twelve hours a day for sixteen consecutive days. Hearing their comments was so interesting for me. It was like an anthropological and social study – how people perceive a transgender body and a hybrid being. After all, I was presenting myself as a half human, half marine creature, and inside of that, I was half woman, half man. Everything was uncertain and uncanny.

“In the way I transitioned, I was chasing an ideal. I wanted to be this desirable creature. But it was more for other people to consume than something I really felt inside.”

Photography RONALD DICK Eyewear KUBORAUM Bracelet OBJECTS INNERRAUM

What did you hear them say about your appearance?

I could hear them roar. Sometimes, what I heard was nice, sometimes, it wasn’t. As queer people, we are constantly under scrutiny and we are judged by others. But, still, those comments can hurt, because in the end, although we fight against society’s structures, we still want to find a place in it.

While I was doing the performance, I had time to reflect. I was thinking about who I want to be and who I’m doing this transition for. That’s when I understood: For as much as I can dream of a new species in my work, I’m still human. And, as such, I want deep connections and human interactions.

The challenge of being part of the trans community and of transitioning is that you start to see other people in such an anxious way that you hide away from them. But I don’t believe in solitude.

There is a risk of becoming bitter due to misunderstanding or rejection by others.

Yes, but I think trans people need to be in the middle of society. They need to be part of the discourse. However, transitioning is not a requirement for that. There’s something so empowering in maintaining your position, maintaining your ideas without having to change and injure your body.

Because, ultimately, your body is not your identity.

Exactly. I was thinking today how beautiful it is to be a woman in a male body, you know? Queer people are there to destroy all notions that human society has created. We are here to shake the terms “man” and “woman.” These terms were created; they don’t mean anything. We can play with them and it feels very empowering to do so.

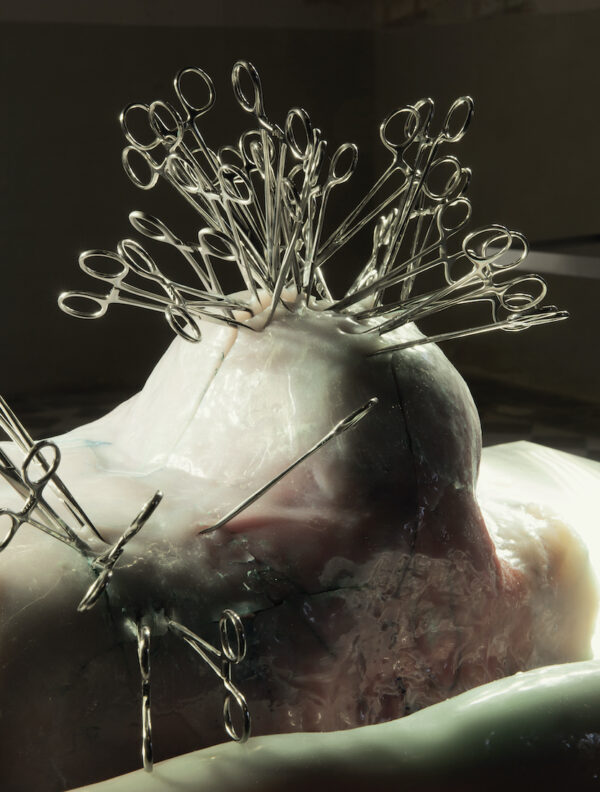

ADRENALINE, 2023

ATTEMPT I, performance and installation, 2023, Courtesy of Mimosa House and Dazed

Displaying yourself to an audience is also an empowering experience, I guess. To hear what people are saying, but to stay in place and endure it seems to me like being in the middle of the sea, standing strong and breaking the waves.

That’s a beautiful metaphor.

It came to my mind because of your love for the ocean, sea creatures and the underwater world, which also plays a significant role in your artistic work. Where does this fascination come from?

I grew up by the sea and on my father’s boat. So I always had a strong connection with the ocean. When you see fish or another sea creature, you don’t ask yourself if that’s a male or a female. The underwater world is such a fluid place.

What would you say has influenced your work the most, besides the ocean?

I think research is what guided me the most and has made my ideas flourish. Every time I read a book that embodies my ideas, I feel stronger. I feel more entitled to talk about what I’m thinking because there is someone else using the same language. A lot of writers have influenced me and helped me to shape my vision. For example, the idea to see the human body, but also the nonhuman body and the machine. These are the three ecologies that a lot of philosophers think about. We can’t separate them. We need to create a compromise between these three layers. This is the core of my work.

“The system has failed. And, therefore, we have to create a new one.”

Photography RONALD DICK Eyewear KUBORAUM Bracelet OBJECTS INNERRAUM

Can you tell me more about the readings that impacted you?

One article called “Portrait of the Homo Aquaticus” was a cathartic moment for me. It was published by the New York Times in the 60s by Jacques-Yves Cousteau. He was a French scientist and oceanographer who co-invented the Aqua-Lung (precursor to scuba gear) and made the first French underwater film. He documented his extensive underwater expeditions in films and television series that captivated generations, showing us this world in a completely new way, with storytelling, music and voice over.

He was not only a scientist but a visionary, a dreamer and a movie maker. He imagined that in the future – that was in the 60s, so that future would be now – mankind would develop so much mechanically and technologically that we would live underwater 80 percent of the time. Because actually, outside of the water, there is less livable volume than in the ocean. So he created this term: Homo aquaticus.

This theory is particularly interesting because humanity evolved from water. It’s the origin of life. So it’s coming full circle.

Exactly. When I read the essay, I was 21 and in my final year at university. I was like: Wow, this speaks so much to me. Cousteau inspired me to do my first underwater installation. The second writer that had an influence on my work was Donna Haraway and her thoughts on the Chthu

lucene. Chthulu is a creature similar to an octopus. It’s also a monster from a fantasy story by H.P. Lovecraft.

Haraway thought of changing the idea of the Anthropocene to the Chthulucene. The Anthropocene refers to the historic moment on planet Earth in which humanity is the hegemonic supremacy. Humanity is so powerful that it has the ability to control and shape planet Earth, but also to destroy it. But Haraway instead speaks about the Chthulucene, in which we as humans impact and embody nature, and become tentacular beings.

“The doctor represents a sort of control, the patriarchy. But we can become our own doctors, we can heal and transform ourselves.”

Photography RONALD DICK Eyewear KUBORAUM Bracelet OBJECTS INNERRAUM

As far as I know, in Haraway’s vision, gender doesn’t exist anymore.

I think she’s a trans feminist. She believes in science and reshaping ideas of gender through technology. And then she has this idea of tentacular thinking, which, to me, was so important to understand that there is not only one way of thinking, but also this tentacular vision of an octopus, which is horizontal and not vertical.

We as humans have a vertical system, our brain controls the other parts of our body. But what if we start to think with our hands, with our feet, with our stomach and so on? This was the starting point for me to create Transgenesis, the giant octopus that I exhibited in London.

So, speaking about transforming and mutating – where do you think it will lead us?

My idea of a human being is a complex structure that is autonomous, keeps changing and keeps transforming itself with its own skills and apparatus, rather than having someone else controlling its body. So, actually, I believe in a human that becomes a machine, but the machine transforms itself and therefore preserves humanity. Of course, my art is an exaggeration. It’s a provocation. But it’s also about thinking of our existence more freely.

And what comes next? I heard you are showing your work in Venice this year.

I’m going to present a new project at the Venice Biennale. It’s about my vision for the future of humanity. About a hybrid being, made out of silicone, that is laid down on a surgical table, and then the creature becomes the machine itself. It operates on its own body with its tentacles. So it all comes together: the human, the nonhuman and the machine. And what is important is that this hybrid creature is not only mechanically controlling its body, but also reshaping it. There is no doctor. The patient becomes the doctor.

That’s important because for me, the doctor represents a sort of control, the patriarchy. When you go to a doctor, you have to obey, because you don’t have the knowledge or instruments to help yourself. But my vision is to regain the power to be able to do whatever we want with our bodies. We can become our own doctors, we can heal and transform ourselves.

Interview by Ann-Kathrin Riedl